Impression management isn’t exclusive to the modern-day. At its root, the theory is fairly simple; people and organizations attempt to influence the perceptions of others in order to become more likable. But impression management doesn’t exist in a vacuum. What happens when competitors get involved? What happens when a company says, “We want people to like us, but more importantly, we want people to dislike our competition?”

In their recently published article, researchers Benjamin Cole and David Chandler investigate impression management theory in a new historical context: the battle for dominance between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse in the late 1800s electricity industry.

Applying impression management theory to a mudslinging media battle

Published by Administrative Science Quarterly, A Model of Competitive Impression Management: Edison versus Westinghouse in the War of the Currents investigates an early example of competitive impression management. During the late 1800s, Edison and Westinghouse oversaw companies vying to become the leading supplier of electricity for homes and cities. Both used some questionable tactics to influence people’s perception of the other company and bolster their own reputation.

In the late 1880s, New York wanted to adopt electrocution as a more humane method of capital punishment than death by hanging. Edison seized this opportunity and proposed Westinghouse’s electricity company as perfect for the job.

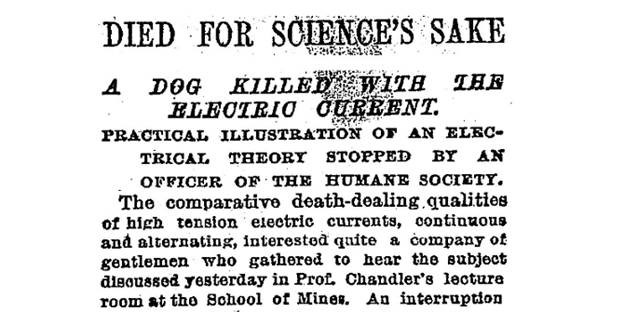

“It was a very underhanded move,” said David Chandler, Associate Professor of Management at the CU Denver Business School. “Westinghouse didn’t want to provide electricity for electrocutions, he didn’t want to be associated with that. This was a devious way of conveying the idea that Westinghouse’s electricity (alternating current) was dangerous, while Edison’s electricity (direct current) was safe.” Edison’s aggressive campaign to tarnish his competitor’s reputation led to even more underhanded tactics, including publicizing animal electrocutions. Edison routinely called the media’s attention to research labs that electrocuted stray dogs using Westinghouse’s electricity. This created the type of sensationalized reporting that goes viral, effectively placing Westinghouse’s electricity in a negative light. The execution of Topsy, an elephant condemned for killing multiple handlers, was one of the most publicized events of this campaign. As long as Edison could control the narrative, he believed he could beat Westinghouse in the War of the Currents.

Competition proves essential to innovation

The War of the Currents wasn’t all negative. It ultimately pressured Westinghouse to make his alternating current better and safer, surpassing Edison’s technological standards. If Westinghouse hadn’t kept innovating to rebut Edison’s campaign tactics, we may not be living with the same product we use today. “This is how competition begets innovation,” Chandler said. “Competition is what makes business so vibrant and so entrepreneurial, and it’s the reason firms constantly produce better products.”

“This has some exciting implications for our understanding of how markets work, and how competition between companies works,” he added. “The outcome is that pressure to innovate forces firms to make their product much better in order for it to win in the marketplace.”

Modern-day examples of weaponizing media attention

Impression management doesn’t include all brand warfare in the media. If activists campaign against an organization (consider Greenpeace vs Exxon), that’s one thing. They each have different audiences, messages and objectives. But when we see two competitors in the same market fighting to control the narrative for their benefit (and executing a strategically developed negative campaign against the other), that’s “competitive impression management.”

A great modern-day example came out of the aluminum debate between Chevrolet and Ford Motor Company. After Ford started using aluminum instead of steel, Chevy took the “materials war” public by mocking Ford’s decision and arguing that steel is safer. One of their ads showed a group of people in a room with two cages: one aluminum and one steel. A bear suddenly enters the room and forces the participants to choose the safest cage. Of course, they chose the steel one. Despite Ford’s assertions that aluminum vehicles were not only safe but also more environmentally- friendly, the company’s market position was weakened by having to go on the defensive.

Professor Chandler also explores a Coke vs Pepsi case in his Strategic Management class. “There’s a famous quote that says if Pepsi didn’t exist, Coke wouldn’t need to invent,” he said. “So in a way, Pepsi makes Coke better.”

Although both companies fight for similar consumers with similar products, they have a healthy duopoly that pressures each other to continually innovate their products. While managers may prefer to have a monopoly because it makes life easier, the absence of competition reduces the need to innovate.

“There’s somebody nipping at your heels,” said Chandler. “It’s constantly reminding you that if you don’t innovate, they’ll take over.”